|

| An early French edition of Lahontan's travelogue. |

I've spent the last week in UT Austin's

Harry Ransom Center reading a book that was once sensationally famous but has since fallen into obscurity: the Baron de Lahontan's

Nouveux Voyages dans L'Amerique Septentrionale, published in English as

New Voyages to North America (London, 1703). After reading less than half, I can safely say that this is an extraordinary book, sparkling with unusual details, spectacular engraved illustrations and a unique narrative voice. Indeed, there's almost something post-modern about the moral ambiguity of Lahontan as narrator - on the surface he appears to scorn the "silly" ways of the "Savages," but the work is also suffused with concealed admiration for what Lahontan calls the "most Natural of Natural Philosophers" who populated the vast North American forests, and the book concludes with a dialogue between the Baron and a semi-imaginary Huron Indian chief (Lahontan calls him 'the Rat') which paints European Christians and their money-driven ethos in a distinctly unfavorable light.

|

| The English title page. |

A bit more information about the somewhat mysterious Loius Armand, Baron of Lahontan (9 June 1666 – c. 1716) can be garnered from the

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, where

an informative entry by David M. Hayne tells us that he was born to a noble French family in the environs of the

town of Pau, on the border near the Pyrenes. Lahontan came to French Canada at a young age, around 17, and moved throughout New France for ten years as a soldier, translator and traveler. Upon return to France he seems to have been deprived of his large inheritance, but he won fame for his writings and maintained a friendship with the great

Liebniz (and also, it would seem, with

Sir Hans Sloane, the botanist, founder of the British Museum and co-inventor of hot chocolate -- on whom more in a later post). Lahontan's

Voyages, Hayne notes,

were based on personal observation of events and practices in New France, of Indian customs, and of flora and fauna. They included an impressive wealth of detail and, except for some exaggeration in the numbers of persons involved, were remarkably accurate in their information. The infrequent occasions on which Lahontan retailed hearsay – for example in his jesting page on the marriageable girls sent out to New France, or in his tale of the Long River – have drawn refutations which by their violence bear witness to his relative veracity elsewhere.

|

| The cartographer Hermann Mole's depiction of the mythical 'Longue River' linking the Great Lakes with the Pacific, seemingly invented by Lahontan along with details of cultures and ecosystems that lay along it. |

Hayne continues:

Quite apart from the information and opinions they communicated about North America, moreover, Lahontan’s works were a compendium of early 18th-century “philosophic” ideas about the folly of superstitions, the vices of European society, the illogicalities of Christian dogma and the virtues of the “noble savage.” The same ideas, better expressed, would be found in the writings of major 18th-century authors: in the fourth book of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), in Rousseau’s Discours sur les origines de l’inégalité . . . (1755), in Voltaire’s L’Ingénu (1767), or in Diderot’s posthumously published Supplément au voyage de Bougainville...

Below are a random sampling of quotations from the English translation of Lahontan's

Voyages, with two engraved plates from the French edition. These are some of the earliest written accounts of the native tribes -- Ottawa, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, and many more -- that populated New France, and the haunting sense of a vanished world and culture is palpable here.

On property and inequality: "They think it unnaccountable that one Man should have more than another, and that the Rich should have more Respect than the Poor. In short, they say, the name of Savages which we bestow upon them would fit our selves better, since there is nothing in our Actions that bears an Appearance of Wisdom... They brand us for Slaves, and call us miserable Souls, whose Life is not worth having, alledging, That we degrade our selves in Subjecting our selves to one Man who possesses the whole Power..." (421).

On food: "Their Victuals are either Boild or roasted, and they lap great quantities of the Broath, both of Meat and of Fish: They cannot bear the taste of Salt or Spices, and wonder that we are able to live so long as Thirty Years, considering our Wines, our Spices, and our Immoderate Use of Women." (422)

|

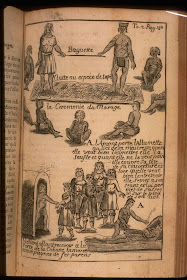

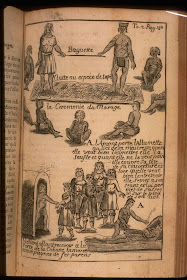

| "The Ceremony of Marriage": a bride and groom prepare to marry, and lovers courting by visiting one another's houses, "accompanied by parents" and without. In the detail at lower right, a suitor visits a young woman bearing a candle - if she blows the candle out, they will sleep together. |

|

| A similar illustration from the English edition, with more details. |

On widows: "When the Husband or Wife comes to dye, the Widowhood does not last above six Months ; and if in that space of time the Widow or Widower dreams of their deceas'd Bedfellow, they Poyson themselves in cold Blood with all the Contentment imaginable ; and at the same time sing a sort of tune that one may safely say proceeds from the Heart." (459)

On men who 'go in a Woman's Habit': "Among the

Illinese there are several Hermaphrodites, who go in a Woman's Habit, but frequent the Company of both Sexes. These

Illinese are strangely given to Sodomy, as well as the other Savages that live near the River

Missisipi." (462)

|

| "Savages going to the hunt," an "infant attached to a branch of a tree," and a "female savage carrying her child." |

And one of my favorite passages, on 'Hunting Women' who 'will not hear of a Husband': "To justify their Conduct, they alledge that they find themselves to be of too indifferent a temper to brook the Conjugal yoak, to be too careless for the bringing up of Children, and too impatient to bear the passing of the whole Winter in the Villages... Their Parents or Relations dare not censure their Vicious Conduct; on the contrary they seem to approve of it, in declaring, as I said before, that their Daughters have the command of their own Bodies and may dispose of their Persons as they think fit... The

Jesuits do their utmost to prevent the Lewd Practices of these Whores, by preaching to their parents that their Indulgence is very disagreeable to the Great Spirit, that they must answer before God for not confineing their Children to the measures of Continency and Chastity, and that a Fire is Kindled in the other World to Torment 'em for ever, unless they take more care to correct Vice. To such Remonstances the Men reply,

That's Admirable; and the Woman usually tell the Good Fathers in a deriding way,

That if their Threats be well grounded, the Mountains of the other World must consist of the Ashes of souls." (464)

An excellent answer from the women, in my opinion! (And we must be careful not to take Lahontan too much at his word in his own censure of these practices - the Baron seems often to tacitly approve of the un-Christian yet spirited and clever responses of his native interlocutors, though he can never admit it outright.) These passage raise some profound questions about gender in North American indigenous societies -- Lahontan's 'Hunting Women' and 'Hermaphrodites' are fascinating and almost entirely unstudied, based on what I've read -- but sadly the documentation for these practices is so fragmentary that they may never be fully understood by historians.

|

| A detail from the 1707 French edition showing what is probably the earliest European depiction of the bison hunts of the Plains Indians - early French travelers like Lahontan called them 'boeufs sauvages,' or wild cows. |

Lahonta's

Voyages are on Amazon

and can also be found

on Archive.org. Those interested in the larger context of Indian, French and British interaction in the colonial American frontier would be wise to start with Richard White's famous work

The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires and Republics in the Great Lakes Region

(1991), which is the authoritative work on the subject and an amazing piece of scholarship, if at times a bit daunting. Maps and engravings from Lahontan's works, which by and large were extremely well-illustrated, can be found on auction sites throughout the web, but the best site to browse is probably

Early Images of Canada, which has

over one hundred images from different editions of Lahontan's travels online in a searchable database.

Ben, I have no clue what or who I clicked on in twitter to bring me to your blog. That said, I am glad. What an interesting and historical find you have read and summarized here.

ReplyDeleteI love the way you relate the best and most interesting parts of the works of Lahontan. Particularly the two-spirited individuals and his observation of native people and their gender and sexual social mores. It's also quite astute to note he seems to appreciate their candor and berate the common European dogma.

You've got quite a choice in literature here... and I will look forward to randomly checking your book reviews and blogs in the future.

I'm a reader of ethnographies, biographies and the like... so such an interesting historical piece is great to see.

thanks,

opinionatedhijabi

-e-

Thanks for the kind words!

ReplyDeleteThanks Ben, fascinating stuff. (btw, last link is borked)

ReplyDeleteJust changed the link to a better one, from the Early Images of Canada site (also added two more illustrations from same).

ReplyDeleteBen, I got rec'd to your blog from slate culture gabfest. Do you listen to it? It is fun.

ReplyDeleteDid your readings in "Nouveux Voyages dans L'Amerique Septentrionale" reveal any practices around mental health, mental illness ... casting out of demons ... etc., I blog on mental health awareness and if Lahontan was specific about male/females roles, it occurred to me maybe he also encountered Noble savage wisdom on "crazy" people.

It has been a particularly Christian/western point of view, that crazy people were inhabited by demons, perhaps because they sinned ...

Lahontan does write that the 'Savages' of New France view illness and all manner of unlucky events as being caused by demons or bad spirits. But he doesn't seem to go into much detail about what a European of his time would have called 'madness.' His only uses of the word are in the context of religion, for instance when he says to Adario, or 'the Rat,' his native interlocutor: "He that is unacquainted with the Truths of the Christian Religion, is not capable of receiving a Proof. All that thou hast offer'd in thy own defence is prodigious Madnefs. The Country of Souls that thou fpeakeft of is only a Chimerical Hunting Country : Whereas our Holy Scriptures inform us of a Paradife, Seated above the remoteft Stars, where God does actually reside..."

ReplyDeleteHowever, I think you'll find abundant examples of what you're looking for in the Jesuit Relations of New France, which are available for free online and have many accounts of spirit/demonic possession and 'madness.'

Just came across a fantastic passage on wizards and spirits from a letter of Lahontan's included toward the end of his 'Voyages,' dated July 4, 1695:

ReplyDelete"The Savages believe that a Watch, a Compass, and a thoufand other Machines are moved by Spirits; for your ignorant and clownifh People form extravagant Ideas of every thing that surpasses their Imagination. The Laplanders and the Tartarian Kalmouks ador'd Strangers for playing Legerdemain Tricks. The Fire-eater at Paris pass'd a long while for a Magician. The Portuguese burnt a Horfe that did wonderful things, and his Owner had enough to do to make his escape, becaufe they took him for a Conjurer. In Afia the Chymists are look'd upon as Poyfoners. In Africa the Mathematicians bear the name of Wizards..."

It goes on in that vein for some time. great stuff. Pg. 906 in my edition.

ben, thx for the response and pointer on "demons and bad spirits". Were there examples of what the "savages" did to treat those with demons? Witchdoctors, shamans, rituals of exorcism? Were those possessed ostracized or brought in closer to the community? bill

ReplyDelete